DMU Pharmacy lecturer Dr Neena Lakhani (nee Nathwani) was born in 1957 in Jinja, Uganda, a city known for lying by the source of the River Nile.

The eldest of three children, Neena’s childhood was idyllic. But at the age of 15 her life changed forever when dictator President Idi Amin gave all 80,000 Ugandan Asians just 90 days to leave the country.

Losing her home and adored pet dog, being threatened at gun point and bribing soldiers to get through checkpoints were all part of her terrified family's escape to sanctuary in the UK.

This is her story…

Neena’s mother and father lived in a six-bedroom home they had built to house them and their young family of three children as well as extended family.

In between school days there were walks in the parks, picnics and swimming, boating on Lake Victoria and - most importantly – a tight knit community that looked after each other.

Neena’s father was a successful businessman. Like tens of thousands of other Indians, he had moved away from the Indian Raj to Uganda, with his family, to seek opportunities in the burgeoning cotton, oil and sugar cane industries.

Neena says: “We had a privileged upbringing and a very British upbringing, learning music and playing guitar and piano. I also played sitar. I really enjoyed life. I had a love for books, swimming and travel; education and improving knowledge was important for us and the community.

“The Indian and the African Ugandans all got on very well. As far as we were concerned there was no such thing as a security problem. We were a close community of friends and there was no animosity towards people because of their ethnicity or their faith. There was no tension at all.”

At the age of 15 Neena and her family’s lives were turned upside down.

In August 1972, Idi Amin – who a year earlier had declared himself president of Uganda following a military coup d’etat - issued a decree banishing all Asians from Uganda under what he called the ‘economic war’.

Families born and raised in the East African state - some for generations - were told they had 90 days to leave behind their businesses, their homes, their livelihoods and their country before all possessions were handed over to Amin’s supporters.

Neena with her class at primary school in Uganda

Neena says: “Things went drastically wrong.

“My father would come back from work and say ‘something is not right. There is something going on with the government and Idi Amin is doing things that are extremely uncomfortable for us.”

Fears were heightened among the Ugandan Asians when Manubhai Madhvani – an Indian-born Ugandan entrepreneur and industrialist – was imprisoned. He was a close friend of Neena’s father.

She said: “Everyone respected Mr Madhvani and the Madhvani family. They were a great success story in the country. I remember I was sitting on the bank of Lake Victora and the whole community came together saying ‘what is happening?’.

“I clearly remember the state of panic in the faces of my aunties and uncles and our friends. We were saying ‘this man (Manubhai Madhvani) is not bad. Idi Amin has to let him go.’ We all thought the government could not get away with it.

“I do not remember the exact date but Mr Madhvani was released and it was then announced that all Asians had to get out of Uganda.

“We were quite sluggish in our reaction and failed to really see what was happening initially. But Idi Amin was serious. The schools were closed down. We had a lovely big house and a dog we adored and three pet parrots. So we decided we would take as much as we could and leave our dog behind because we would come back for him. We were going to the UK as we had British passports.

“We packed what we could into boxes, such as music equipment, our books – I loved my books – and photographs my Dad had taken. He was a very good photographer.

“We then had to take them to an area where the military could inspect everything before we could ship them out to the UK.”

It was during one of these inspections that Neena realised hers and her family’s lives were no longer safe in Uganda.

“I had never seen a Kalashnikov rifle before”, Neena says, clearly still shaken by the events that unfolded as a 15-year-old girl.

“One of the military had one and indicated to my mum not to come anywhere near me. Then he said ‘I am going to take away your daughter’ and pointed that gun right at my forehead. All I remember is looking helplessly towards my mum and seeing the terror in her face.

“Then he took the barrel away from my head and walked away laughing saying ‘watch out. I am going to come for your daughter’.

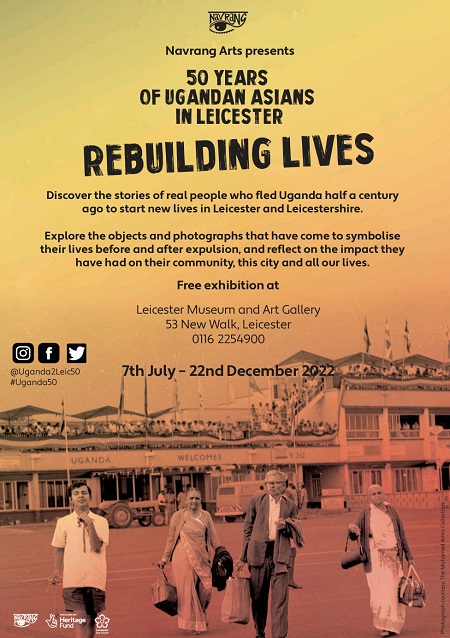

An exhibition tells the story of Leicester's Ugandan refugees

“We had already heard about harassment and kidnappings so we left our parcels as they were and came home.”.

As they prepared to leave the house and head for the airport, Neena’s father said ‘we’ll be back’ and he left behind money for people to look after the pets and the house and the garden.

“It was as if we were going on holiday, loaded up with bags and so on. We wept as we drove away. We never did return.”

Neena had to travel from Jinja to Kampala and then get a bus with the other refugees from Kampala to the airport in Entebbe.

“We were in a convoy of four cars and had to get through four military checkpoints between Jinja and Kampala,” Neena says. “At the first checkpoint my dad left some money so the soldiers let the convoy through. The same happened at the second checkpoint.

“The third checkpoint was at the Mbira Rainforest. We were all taken out of our cars by the military and my mother and I were separated from my dad and brothers. They marched me and my mum into a clearing in the forest.

“Now Mum and I had long hair and Mums hair was kept in a bun and mine was in two long plaits. So they pointed their guns at our hair and told us to let it down. They were looking to see if we had hidden any jewellery. When they checked me I was absolutely terrified.

“My father shouted ‘let them go. Whatever money you want I will give to you, or take me instead’.

“The military took the money my dad offered and let us through.

“We reached Kampala and were shown to our buses. At the airport we loaded all of our luggage and got on the plane. We were all talking and for the first time ever in our lives my Father turned to us and told us all to shut up. It was so unlike him and there were tears welling up in my eyes.

“He said: “There is a reason why I am keeping you quiet”. He was tense and worried.

“After the plane took off we crossed the Uganda/Sudan border and my dad said; “Now I am relieved”. At that point first class and economy class merged and we sat as a community, flying to London.”

The family had relatives in London and did not have to go into a camp. But they were used to a big house with six bedrooms and there were now 10 members (including extended family members) in a house with 2.5 bedrooms.

Neena and her two younger brothers started at a school in Edgware and found it easy to mingle and easy to find friends “partly because so many children from this mass exodus were at the school”.

So how did Neena end up in Leicester?

“We had known about Leicester for a while. I loved my vegetarian food and we used to visit Leicester and Bobby’s on Melton Road is a place I remember well because Mr Lakhani who ran it at the time was from Jinja. I remember saying: “I am home. I am home’.

“I met my husband in London, and we moved to Leicester because of business commitments and, I have to be honest, I cannot live anywhere else now. I love the city.

“I became a pharmacist in London, and worked hard for it. Everyone in Uganda was brought up and educated to have a vocation in life. A lot of parents who arrived in Leicester had to work in a factory for the first time to earn a living. They saw how hard it was and didn’t want that for their children. With a vocation, your children could be put anywhere in the world and they would be able to work.

“That ethos came from Uganda. We all saw the pain and the trauma our families went through to get here.

“That is why we all have so much respect for families that are refugees. I feel for the Ukrainians, and the Syrians and the Afghans. I know what they are going through to have to leave home and make a living in another country

“I am one of the people who can say “Thank You Great Britain. We will not depend on you. We are a very proud community and we will make our own life here”. We took any job that came and lived according to our means. We believed in education, believed in sympathy and empathy and a shared humanity.

“I still ask people when I see them if they are from Uganda. We recognise people from East Africa. There is a behaviour that is very, very unique to us.

“Although I love Leicester, if people still ask me where home is, I say Uganda. I have never been back but I plan to take my family there some day.”

• As we mark 50 years of the Ugandan Asian’s exodus, and the contributions they and their families have made to our city, we are keen to speak to more DMU staff, students and alumni about theirs, and their families’, recollections of the journey from 1972 to 2022. If you would like to see your family story on the DMU website then please send your name, connection to DMU and contact details to news@dmu.ac.uk and we will get in touch.

Posted on Friday 22 July 2022