As part of the celebrations for DMU's 150th anniversary, Journalism lecturer Jeremy Clay asked the university's special collections team to choose their 10 favourite things from the archive:

Take one flight of stairs down to the basement of the Kimberlin Library. Push through two sets of double doors, and walk on, past the back issues of the Radio Times, the stacks of daily papers and the files of periodicals ranging from the New England Journal of Medicine to Schmuck magazine.

Go on, go on, go on, as if implored by Mrs Doyle, and you’ll come to an unassuming room tucked away in a corner.

If a university has a heart, you’ll find De Montfort’s right here, in the Special Collections department.

Its tightly-packed shelves and climate-controlled storeroom hold pretty everything you’d expect to find in an archive of a major university.

There are the prospectuses going right back to 1897, and DMU’s former life as the Municipal Technical and Art School. There are the Very Important Papers relating to the running of the university - the minutes of meetings, the annual reports and whatnot. And there are the student rag mags from the 70s and 80s. Let’s just break off for a moment and have a quick flick through a few, shall we? Hmmm … ah … oh dear … ooof … urgh … for pity’s sake … no!

But amid all the customary keepsakes of scholarly life there are plenty of things you wouldn’t necessarily expect to find. A Lyonnais silk merchant’s sample book from 1837, seized at customs (insert your own Brexit remark here, depending on viewpoint). A collection of a space-themed stamps from the Soviet Union. An entire shelf full of books about chess, that leads on to – gasp! - several other shelves of books about chess. A collection of artefacts from the Ski Club of Great Britain (held in a city which the Mountain Guide lists as having the 3,884th tallest peak in England). A tablecloth the Queen fleetingly leant upon to sign the visitors’ book at DMU.

And that’s the kind of stuff that interests us here: the wait-now-what-now? bits and bobs you’ll unearth if you have a good old rummage around down here. To mark the 150th anniversary of the university, Special Collections manager Katharine Short, assistant archivist Natalie Hayton and archives assistant David Millns did just that, and picked out their 10 favourite oddities and curios from the vaults. A bit like Cash in the Attic, then, but set in a basement. Cache in the cellar, if you will.

1. A hoard of Civil War weapons

You wouldn’t want to get on the wrong side of DMU archivist Katharine Short.

Why would you? She’s wise, affable and generous with her time. But also: she has a sword.

It’s squirreled away safely in a store room, in case anyone questions the wisdom of leaving weaponry lying around in a library. And even if it somehow fell into the wrong hands, the blade is blunter than a Yorkshireman asked to list the merits of Lancashire.

How old is it? “Civil War, with Victorian restoration,” says Katharine, picking her words carefully. “It’s lost in the mists of time,” she says. “I don’t think it was ever brandished in the heat of battle.”

It’s part of a set of armour and weapons – including breast plates and helmets and two fearsome-looking halberds - that used to hang on the walls of the medieval chapel at Trinity Hospital in the Newarke.

This part of town was once the flexed bicep of Leicester’s military muscle. In the 17th century, the Magazine Gateway was used to store arms and munitions. Later, it was part of a barracks with a drill hall and a parade ground for the militia where the Hugh Aston building now stands. Perhaps it’s not too surprising to find the nearby chapel was also packing heat.

Once a year, when the Michaelmas fair came to town, the armour was dusted down and used for a spot of Civil War cosplay on Highcross Street.

“Here may be seen the grotesque ceremony of the poor men of Trinity Hospital, arrayed like ancient Knights,” tutted Susanna Watts’ 1804 travelogue A Walk Through Leicester, “having rusty helmets on their heads and breast-plates fastened over their black tabards.”

The sword, it is thought, was used for funeral processions. The hilt is decorated with a faded painting of a Wyvern, the two-legged dragon that squats atop the Leicester coat of arms and stands guard on landmarks across the city.

“The sword is our party piece,” says Katharine. “It’s always good to get out. It gets a lot of ooohs.”

Sometimes when she’s asked to give a talk on the contents of the archive, she’ll bring along the sword and its companion piece, an arm guard known as a buckler, which bears the cinquefoil symbol of Leicester.

“School kids love it,” she says. “I’ll point out the cinquefoil on the shield and ask ‘where have you seen this before?’ and someone will shout: ‘that’s on the bins!’”

2. A box of alarming dolls

In ordinary times, the DMU library is open 24 hours a day, but the archive closes promptly at 5pm. It’s probably all for the best. You wouldn’t want to be there much later than that; not when it gets dark; not when there’s no-one else around; not with the box marked Beautex sitting on the shelves.

Katharine lifts it down and takes off the lid to reveal a sight that would give Chucky the heebie-jeebies: six dolls with jaundiced skin and 1,000-yard stares gaze unblinkingly out at us.

“It’s like looking into a plague pit,” she says

But it’s not the dolls themselves that merit a place in the archive. It’s what they’re wearing: bonsai outfits made by the Leicester firm William Baker, cannily pitched to match their own collection of jammies for kids.

William Baker was a manufacturer of underwear and kids’ clothes which was based in what’s now the John Whitehead building on the Newarke. It ceased trading a couple of decades ago, amid a miserable tumble of closures of grand old Leicestershire textiles companies.

So how and why did these dolls end up in the bowels of the Kimberlin Library? “We have a long history of training people in the textile trade,” says Katharine. “This collection is part of Leicester’s industrial history, and the history of today’s campus.” Which is a cheerier explanation than the plausible alternative: that they sat up suddenly one moonlit night in the William Baker factory, twisted their heads towards the DMU campus and jerkily walked over here, all by themselves.

3. The oldest book in the library

There are more than 400,000 books in the DMU library. If you laid them all out, side by side, in a line stretching from the steps of the Kimberlin building … well, a vexed librarian would soon appear and ask you what on earth you were playing at.

The oldest of the lot dates back to 1474, or maybe the year after, and was printed in Strasbourg – now Leicester’s twin city, of course - before the first press had reached England.

This is volume three of the Postilla super totam Bibliam, Franciscan scholar Nicholas of Lyra’s whopping commentary of the bible, which became an influential text in the middle ages.

It’s bound in pigskin, stripped from a beast that was merrily truffling around almost 100 years before the birth of Shakespeare, and to be honest it smells a little musty. Then again, who among us wouldn’t after half a millennium?

The pages are made of linen, says Katharine, leafing through the book. She’s got an A-level in Latin, and is soon following the text and muttering contentedly to herself. But the significance for DMU, or more accurately the university’s earlier manifestations, is not in the words on the page.

“We never taught theology here,” she says. “It can only have been used to study as an object. The value isn’t for what’s written but the book itself.

“Leicester had a thriving printing trade, and we provided most of the training for it. This would have been used for examples of typography, lettering, binding and leatherworking.”

4. The oldest object in the archive

There’s a quick and easy way to convince yourself you’re coming down with something nasty.

1. Ask to see the oldest artefact in the archive at DMU.

2. Handle it.

3. Google it, to see what else happened in the year it was created, and discover it dates back to the very height of the Black Death.

If the bubonic plague makes a belated comeback, then – and 2020 might still have a few more tricks up its sleeve - suspicion might fall on item number 3071 CAD/004/004, a deed no bigger than an envelope concerning two patches of land in the hamlet of Nordley in Shropshire.

There are two Nordleys in the county, according to a helpful assistant at the Shropshire Archives.

One is on the map: a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it sort of place, strung out along the B4373 between Ironbridge and Bridgnorth. There’s a handful of socially distanced houses, a snuggler-sized wooden bus stop, and that’s about it.

The other is a deserted village called Kingsnordley, which lives on as a manor house and fishing lake. That’s the most likely one for this artefact, in the considered opinion of the Shropshire Archives.

Either way, it’s possible that the most notable thing about Nordley – whichever one it actually was - lies roughly 80 miles east, in the archives of De Montfort University. It’s a document written on a Friday after the Feast of St Pancras, in the 23rd year in the reign of Edward III – or 1349, if you prefer.

“How cool is that?” says Katharine. “You can sit here and hold something from 1349.”

And yes, you can actually hold it. You don’t need gloves.

At first, that seems reckless. Sacrilege, even. After all, it goes against everything we’ve learned from watching artefacts being reverently handled on TV. But the argument about the pros and cons of wearing gloves, it turns out, divides archivists just as surely as that dress on the internet that might have been black and blue, or white and gold, or something.

“In handling most archival documents, gloves are more of a hindrance than a help and they can actually pose a threat,” says a blog on the National Archive site. Gloves can dull your senses, it warns. Gloves can make you clumsy. Gloves can catch on fragile or previously damaged edges. Gloves get filthy. A troubling passage to read, all in all, for think-skinned members of the Worshipful Company of Glovers.

Katharine, you’ll have already guessed, is Team Hands. It’s much better to feel a document when you hold it, she explains: your fingertips are more sensitive. Anyway: coffee spills and leaky pens are by far the bigger dangers to artefacts.

Back to the deed. In 1349, as the Black Death wiped out great swathes of the population of England, a group of men with surnames that would make tolerable scores in Scrabble met up for a real estate deal. Richard Madok of Nordley transferred his land to William de Fililod. Richard Yyer, Richard le Yonge and Thomas de Fililod served as witnesses.

“You can see the remnants of the seal,” says Katharine, pointing to a lump of black wax dangling off the parchment that was heated up 100 years before the birth of the unfortunate pig which ended up binding the Postilla super totam Bibliam.

We probably won’t know why Richard Madok gave up his land – but given the black death claimed the lives of an estimated 60% of villagers in nearby Alveley, there’s a fair chance it had something to do with chills, high fever, muscle cramps and ultimately a 6ft deep hole in the ground – but there’s one question we can tackle: why does DMU have this document? “Again, it would have been for teaching,” says Katharine. “It demonstrates the skill of calligraphy.”

5. Prototype toasting fork

By day, Frank Watson was a policeman. By night, he was a drummer in a dance band. If the Leicester Mercury didn’t seize the chance to dub him the Beat Bobby … well, more fool them.

Frank was something of a celebrity in Leicester, thanks to his Saturday night stints as the leader of the house band at the city’s Bell Hotel, a handsome Georgian-era coaching inn which had counted Charles Dickens among its guests, but which was demolished in the 1970s when Leicester, in one of its periodic bouts of civic myopia, persuaded itself that the Haymarket Centre would be an upgrade.

But it’s not his paradiddling prowess nor his thief-collaring skills that earned Frank a place in the DMU archives. He’s immortalised here for his services to breakfast technology.

During the First World War, Frank was a student at the Municipal Technical and Art School, one of the earliest incarnations of an institution that could rival Sean Combs for name changes.

Around 1917, the engineering students at the college were set a challenge: to improve the toasting fork.

There was a problem with toasting forks, you see. You had to the turn the bread, to brown it on both sides. That involved a) effort and b) letting out an alarmed yelp and waving your fingers around to cool them off.

Frank’s canny solution is fashioned out of wire and looks a little like the skeleton of Professor Yaffle, from Bagpuss. It has a flipping mechanism. When one’s side’s done, give it a vigorous wobble and – ta-da! – the other side is good to go.

As he put the finishing touches to his fork, maybe young Frank let his mind race ahead to the day when every home in the land toasted their bread the Watson way. Perhaps he allowed himself to imagine a sprawling factory site with his name over the gates; a chauffeur-driven car whisking him home to a stately pile in the Leicestershire countryside; his face on the cover of Toasting Fork Monthly’s People of the Year issue…

… although probably not. At any rate, the first electric pop-up toaster was patented four years later. Bah.

6. One pair of baby’s corrective shoes (used)

Cast your mind back to the lessons you learned in Osteology 101. The thigh bone, you’ll recall, is connected to the, , hip bone.

As it turns out, things are a little bit more complicated than that.

The top of the thigh bone – the femoral head - is rounded like a ball, and sits inside the hip socket. Except sometimes it doesn’t.

When the hip socket is too shallow, the femoral head isn’t held properly in place. It’s known as hip dysplasia, and about one or two babies in every 1,000 – girls more commonly than boys - need treatment for it.

These days an osteopath will prescribe a fabric splint called a Pavlik harness, but that’s not always been the case.

Katharine picks out a tiny pair of shoes which have been secured to a metal plank, like a set of small skis designed by a sadist.

“This always gives me the willies,” she says. “It’s pretty grim”

These shoes, with 19/5/52 engraved on the foot of the plate, are just one of a stockpile of medical curios that De Montfort University inherited when it merged with Charles Frears College of Nursing and Midwifery. There are anatomical models and charts, medals, uniforms and various pieces of alarming equipment that might not look too out of place in the props department for an upcoming sequel to SAW.

The collection used to be a little grislier still. “I’ve got rid of the human bone, I’m afraid,” says Katharine, mysteriously.

7. A book of fabric samples, 1907

“You can have any colour you want as long as it's black,” Henry Ford told his early customers, and you’d be forgiven for thinking much the same applied to men’s suits at the start of the 20th century.

Not so. You could have dark grey as well, judging by this book of fabric samples from 1907. Oh, and a greenish-blue, although, granted, on reflection that has more than a hint of black about it. They were offered by a firm that might be called R & L S, or maybe R L & S - no-one’s quite sure. This was their spring and summer range, by the way. The colours in the winter one might not have been quite so happy-go-lucky.

The patterns book, which was bought for £16 by Leicester Polytechnic, probably as a show-and-tell for textiles students, concertinas into one long stretch of sober samples, for the benefit of customers who like to combine browsing for fabric with an invigorating stroll.

“No one tells you how much of archive work involves crawling around on your knees,” says Katharine, as she unfolds all 25ft of it across the floor of the archive.

And there they are: the complete range of choices in the area of “suitings and trouserings” for the colour-shy gent of the early 1900s: from drab moles to Derby tweed to serges and whipcords. “My favourite is the fancy vestings,” says Katharine. If nothing else, it might be worth asking to have a quick look if you’re stuck for a band name.

8. Sweets from the 1960s (unopened)

If the bottom ever falls out of the archive market, Katharine might squeeze a little mileage out of flogging the out-of-date confectionery in the collection.

“I could probably do a tuck shop for a morning,” she agrees. “Although environmental health would definitely have an issue with it.”

The stash of sweets – some dating back to the 1920s - are part of an extensive collection of papers, adverts and product packaging relating to Fox’s Confectionery, the Leicester firm famed for its Glacier Mints.

The company was founded by Leicester grocer Walter Fox in 1880, and had its factory on York Road, with its headquarters round the corner on Oxford Street. “We take collections relating to the campus site,” Katharine explains, although there is a direct link to DMU too.

Fox's Glacier Mints were invented by Walter's son Eric, and the instantly recognisable logo of a polar bear standing on one of the mints was designed by Leicester College of Art graduate Clarence Reginald Dalby, who went on to illustrate the Thomas the Tank Engine books.

The polar bear proved so popular, the firm paid a hunter to kill a real one, which was then stuffed by a taxidermist and put on display, safe in the knowledge that Twitterstorms were a long, long way off.

The tin on the table in front of us doesn’t contain Glacier Mints but travel sweets from the 1960s, glucose treats to the keep the peckish motorist going in the gaps between casual drink-driving.

It was picked out by archives assistant David Millns, who was charmed by the Spam-style key on the tin. “As a millennial, the idea of having to unlock your sweets blew his mind,” says Katharine.

9. Kazakhstani bank note (framed)

There’s a box in the archive that’s the equivalent of the cupboard under your stairs: the place where you stick the stuff you don’t quite know where else to put.

In here you’ll find some of the corporate gifts given to the university down the decades. A tea cup and saucer from Russia, for instance. A keyring, from Egypt. A trophy from India. A plate from Lithuania. And this framed 200 tenge bank note from Kazakhstan (currently available from £4.54 on eBay).

But as Newton told us, for every action, there’s an equal and opposite reaction, which presumably means there are keepsakes from Leicester in the basements of libraries at universities around the world: an album of Showaddywaddy B-sides, perhaps. A box of shuddersome William Baker dolls. A keyring showing the Haymarket Centre. Which begs the question: what’s the Kazakh for ‘oh, you shouldn’t have’?

10. A pair of floppy disks

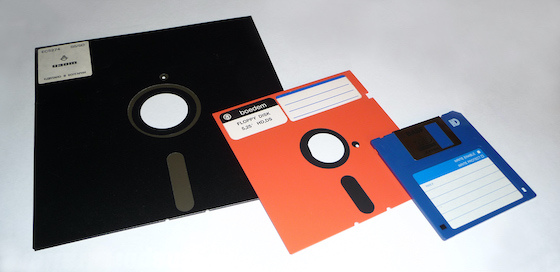

They say today’s science is tomorrow’s technology. But tomorrow’s technology often turns out to be the next day’s trash.

Take floppy disks, for instance. They first went on commercial sale in the 1970s and by the mid-1990s there were an estimated five billion of them in use. And yet in 2018, a survey by YouGov found two-thirds of kids didn’t have a clue what they were.

In the space of two decades, the format went from being ubiquitous to obsolete. It’s a lifespan that would earn the empathy of a fruit fly.

For the final part of this round-up of the oddities in the DMU archive, Katharine pulls out a pair of floppy disks, containing papers from a librarians’ conference held at the university in 1994.

No! Wait! Come back! The disks aren’t really the point what’s here, and nor is what’s on them. It’s what they represent: the archivist’s age-old dilemma – the decision over what to save, and what to ditch.

“You have to make value judgements,” says Katharine. “You apply your knowledge and your experience, and you keep your fingers crossed. But sometimes you’ll get it wrong.

“There are all sorts of stories in archive circles of people saying ‘we have got this massive collection of traffic reports from the 1930s and 1940s, and no one has ever looked at them, so we’re going to chuck them out.’ And then two weeks later someone comes along and says ‘I’m studying traffic accidents from the 1930s … ’”

Katharine hasn’t yet decided what to do with the disks. She thinks they’ll probably go. The papers will have been published. There’s no need for them.

“You can’t keep everything,” she says, with the faint tone of someone who hasn’t entirely convinced herself.

Posted on Friday 18 September 2020