by PhD student Mark Orton

In death, as he was in life, Diego Armando Maradona simply was Argentina.

When he died at the age of 60 this month, we saw mirrored in public reaction to the news the very best and worst of Argentina. It seemed a natural extension of the manner in which, throughout his life, the legendary midfielder had embodied all the complexities and paradoxes of his homeland’s national identity.

The declaration of three days national mourning by President Alberto Fernández for a footballer who transcended sport to become national icon, signalled the biggest outpouring of national grief since the death of Eva Perón in 1952, the only figure in Argentine history to match his mythical status.

Deep-seated footballing enmities were put aside as distraught Boca Juniors fans embraced their counterparts from River Plate, but against this was contrasted the worst excesses of celebrity culture and political opportunism. The elevation of football hooligans of Maradona’s acquaintance like Rafa di Zeo to VIP status at the wake in the presidential palace reflected questionable judgement, as did the government’s populist decision to effectively abandon quarantine in the fight against COVID-19, which has already killed 38,000 Argentines, so that the multitudes could converge on the Casa Rosada to pay their respects to their idol.

Born in Lanús in 1960, Maradona grew up in poverty in the shanty town of Villa Fiorito in the industrial suburbs of Buenos Aires. With Italian and indigenous heritage he was the product of two migratory currents that shaped Argentine society in the twentieth century: mass European immigration and internal migration from the provinces to the capital. When they moved from the north eastern province of Corrientes to Buenos Aires in 1955 in search of better work opportunities. Maradona’s parents were just two of a migratory wave of over one million cabecitas negras, ‘little blackheads’ from the provinces that formed an underclass within the working-class that so readily supported the rhetoric of social justice propounded by Juan Perón’s movement in the 1940s and 1950s.

While Maradona never forgot his roots, and while his political friendships with Fidel Castro, Evo Morales and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner gave him a platform to advocate for the poor in Latin America, paradoxically his materialist instinct to flaunt his wealth and demonstrate his social climbing showed itself most obviously with his ostentatious 1989 wedding in Buenos Aires to Claudia Villafane. While he was telling Pope John Paul II to sell the works of Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel to help the poor, Maradona spent US$30,000 on his wife’s wedding dress.

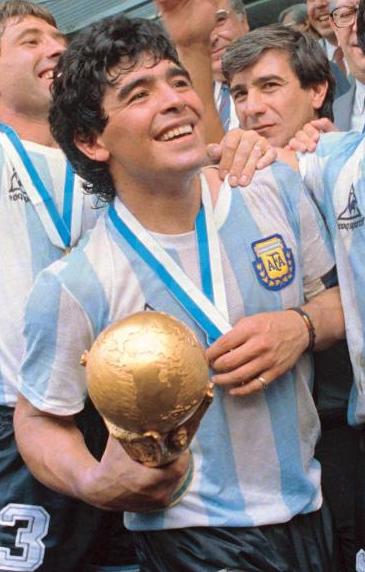

Maradona’s legendary status in Argentina, as the country’s greatest ever player, was forged as he captained his country to World Cup victory in Mexico in 1986. The singular skill he possessed and the sheer joy he seemed to take in displaying it embodied the concept of la nuestra - ‘our way’ - a mythical footballing style unique to Argentina that was fomented in the pages of the magazine El Gráfico by writers such as Borocotó in the late 1920s. The evocation of la nuestra was part of a wider discourse of nationalist revisionism that sought to recalibrate Argentine identity to assimilate the immigratory wave from Europe over the previous half-century into a unified society.

Key to notions of la nuestra were the transformation of Argentine football from were considered its regimented origins in the British public schools, symbolic of British economic domination at the turn of the twentieth century, considered by revisionists as the origins of all Argentina’s ills. Thus despite Anglo-Criollos such as Harry Hayes playing an important role in the diffusion of the game to the popular classes alongside other immigrant groups, Argentine football was said by Borocotó to have been ‘nationalized’ by essential ingredients only to be found in Argentina. Thus, a mythical style developed in the working-class districts of Buenos Aires in which the pibe, or street-kid, developed his skill with a pelota de trapo - ball made of rags - in the potrero or urban wasteland, in untutored peladas or kickabouts. In reality, this simply mirrored the development of working-class football in Edwardian Britain. The best players were those who used their viveza, or street-smartness, to greatest effect, deceiving their opponents and stretching rules to their limits.

As a boy, Maradona developed all of these elements to become the Pibe de Oro, ‘Golden Boy’, telling an interviewer when aged just 12 that his three dreams were to play in the First Division, wear the Argentine shirt in a World Cup and to win the World Cup trophy. In 1986 he achieved the last of these, with his life-defining moment coming in the quarter-final match against England. His two goals highlighted both sides of la nuestra and wider self-perceptions of Argentine identity, both products of the potrero. The first, scored with the infamous ‘Hand of God’ was classic viveza, the cheating to get ahead used by the Argentine political class that has bedevilled the country almost since independence in 1816. His second a piece of genius, born of hours spent as a kid honing his skills in the peladas in Villa Fiorito.

That his greatest moment should come against England only added to his idolisation, notwithstanding the Falklands/Malvinas conflict of four years earlier, beating the English neo-imperialists was essential to the narrative of Argentine identity and Maradona’s reputation as its greatest exemplar despite his personal faults and indiscretions later in his career which besmirched Argentina’s image abroad. As the Argentine sociologist, Juan José Sebreli wrote of Maradona in Frauds and Martyrs: ‘It’s always someone else’s fault, never his own, [a feeling of] victimisation so frequent in Argentina’.

An allegory for the country itself.

Mark Orton is completing a PhD with the International Centre for Sports History and Culture

Posted on Tuesday 1 December 2020