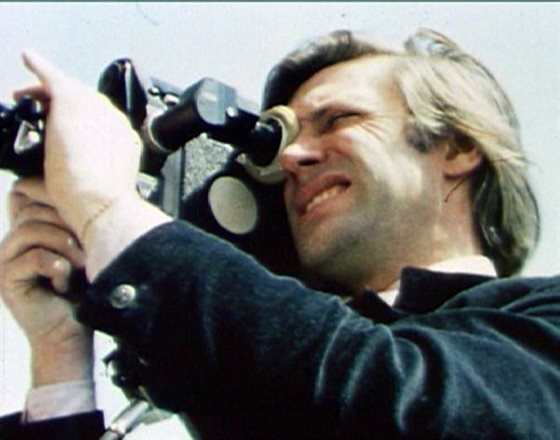

Pioneering film maker Peter Whitehead, who died this week aged 82, captured the raw energy of the Sixties counterculture like never before. His archive is held by De Montfort University Leicester (DMU)'s Cinema and Television History Research Institute. Here Professor Steve Chibnall and Alissa Clarke, curators of the Peter Whitehead Archive, document his life:

Although he will probably be remembered as the film-maker who definitively captured the emerging culture of rebellion in London and the USA in the second half of the 1960s, Peter Whitehead was a Renaissance man of extraordinary breadth. As a genuine polymath, he generated enough career paths for half-a-dozen of his peers, and had enough talent to excel in most of the pursuits which he adopted.

Peter Lorrimer Whitehead was an only child, born into a working-class family in Liverpool in 1937. He knew little of his father, who worked as a plumber in the docks before leaving for military service. Whitehead spent World War II in a variety of Lancashire towns as his mother moved from one factory to the next, eventually finding himself in Carnforth around the time that Brief Encounter (1945) was filmed there. His returning father took the family to London, where they lived in one room of a centre for the homeless while he tried to establish a plumbing business, but died of cancer a short time later.

The young Whitehead was obsessive about trains and often skipped school to spend time at railway stations, so it is all the more astonishing that he managed to win one of the post-war ‘Guinea Pig’ scholarships to Ashville College, a public school in Yorkshire. There he learnt how to speak like a ‘gentleman’, captained the rugby team, and discovered his bi-sexuality as well as a talent for music that enabled him to become the school organist. His academic performance gained him a university scholarship to, appropriately, Peterhouse College, Cambridge to study Physics and Maths. However, he first did two years of National Service as a training officer in the Army, during which he also married model and actress Diane Leigh, who he had met in Brief Encounter fashion in a railway waiting room. The relationship would produce two daughters, Sian and Tamsin.

His time as a Cambridge science student brought him into contact with soon-to-be-famous characters such as David Frost and Syd Barrett and with the man who would become his assistant director and a significant film-maker and artist in his own right, Anthony Stern. Whitehead also worked for Nobel-Prize-winning biophysicist, Francis Crick, but gradually became disillusioned with the idea that life’s mysteries could all be explained by science.

After a road to Damascus moment in the Egyptology rooms of the Fitzwilliam Museum, he developed a profound interest in mysticism, mythology and altered states of consciousness that would inform the remainder of his life. ‘I walked around the displays, feeling as if I had arrived’, he later recalled. ‘I knew in some way, I was now “at home”.’ His other growing passions were for painting, film and other creative pursuits. He acted in student productions and contributed to student journals and the Cambridge Evening News, but increasingly conceived his life as a quest for meaning and understanding within what he called ‘the fractured context of my own life’.

In 1963, now very much a self divided between science and the arts, he was accepted by The Slade School of Art as a postgraduate student of painting, but he gravitated towards Thorold Dickinson’s new Film Department, becoming one of its first students.

Peter (seated) at the launch of the Peter Whitehead Archive, June 2016

He began to make short films, including one, The Perception of Life (1964) on the aesthetics of science that perhaps sought to integrate his divided self through what he termed ‘a fusion of irreconcilable opposites’. Leaving The Slade, Whitehead developed a career as a professional film-maker, supplying footage of the emerging ‘Swinging London’ to Greek and Italian television, and he set up his own publishing company, Lorrimer Books, dedicated mainly to work of contemporary European directors, particularly Jean-Luc Godard.

It established his fiercely independent practice of self-publishing that he maintained to the end of his life. Fortuitously, he took his camera to the extraordinary festival of ‘Beat’ poetry at the Royal Albert Hall in the summer of 1965. The resulting Wholly Communion (1966) is now celebrated as the documentation of the founding event of London’s Counterculture. It attracted the attention of Andrew Loog Oldham, the manager of The Rolling Stones, who employed Whitehead to make a documentary of The Stones’ Ireland tour – Charlie is my Darling (1966) – and a number of promotional films for his record company. As a consequence, Whitehead is now thought of as a founding father of the pop video, although classical music remained his first love.

He combined lucrative record company commissions with two larger projects, a film on Peter Brook’s anti-Vietnam War play US (1967), and a critical documentary examining the phenomenon of ‘Swinging London’ and the American influence on British culture: Tonite, Let’s All Make Love in London (1967), for which he famously filmed the first professional footage of Pink Floyd. But the work was undertaken in a vortex of ill-health and promiscuity. At the same time, he fathered his only son, Harry, born to the celebrated actor and charity worker, Coral Atkins.

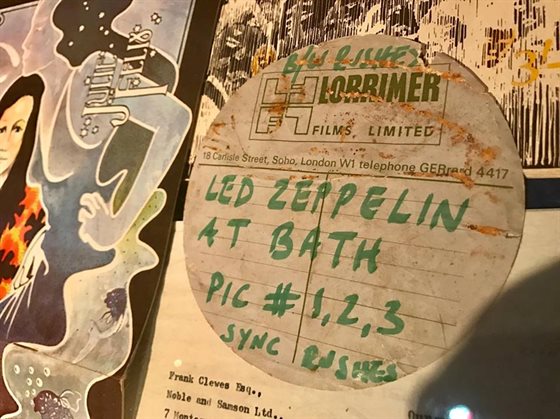

Peter Whitehead filmed Led Zepplin performing in Bath

Accepting the offer of funding for a film about American society, Whitehead then left for New York with his lover, the Italian super-model Alberta Tiburzi, and Anthony Stern to make The Fall (1969), an indelible record of one of the most turbulent years in US post-war history. Marin Luther King was assassinated when Whitehead arrived and Robert Kennedy when he left. The experience both radicalised his politics and led to a nervous breakdown. He re-emerged to film a concert by Led Zeppelin at the Royal Albert Hall in January 1970, but he was moving away from imaginative reportage towards the making of art works in collaboration with creative women like the British feminist collagist, Penny Slinger, and the French artist, Niki de Saint Phalle. He filmed and played a falconer in the latter’s autobiographical Daddy (1973), and he revisited some of his sixties’ work in the partly autobiographical Fire in the Water (1976), which featured another of his glamorous lovers, the film star Nathalie Delon.

For the next 15 years, Whitehead effectively dedicated himself to falconry, scouring the globe for rare bird’s eggs, which often involved dangerous mountaineering, sometimes with his friend the poet, Ted Hughes. His obsession with these sacred birds of prey developed a level of skill and knowledge that led to his appointment as the chief falconer of the Saudi Royal Family. He was director of the specially built Al-Faisal Falcon Centre throughout the 1980s, before returning to England at the outbreak of the Gulf War.

By this time, he had married the Dido Goldsmith, the niece of Sir James Goldsmith, to whom he was introduced by their mutual friend, Bianca Jagger. Whitehead would have four daughters with Dido, including the eldest, Robyn, who became involved with the circle of musician Pete Doherty and died of a drug overdose in 2010. His chief creative outlet during the 1990s and the new millennium was novel-writing and publishing, including his mystical ‘holographic’ novel The Risen (1994), which he regarded as a premonition of the serious heart attack that he suffered in 1996. This medical emergency forms a centrepiece for the fictionalised documentary on Whitehead, The Falconer (1998) made by Iain Sinclair and Chris Petit.

As part of his convalescence following his emergency bypass operation, Whitehead took up pottery and again developed his skill at this new art-form to an exceptionally high standard. Alongside his autobiographical trilogy Fool That I Am (2013), Whitehead’s final major work was the provocatively-titled film Terrorism Considered as One of the Fine Arts (2009), a two-and-a-half-hour film based on this 2000 novel of the same name. He received a number of international awards for his films and the accolade of a 1,500-page double-issue of the academic journal Framework (2011) dedicated to a retrospective of his work in all media. His papers and many of his art-works were deposited in the archives of the Cinema and Television History Institute at DMU.

Peter Whitehead was possessed of a unique, and highly-distinctive, creative spirit, film-star looks and a magnetism that attracted the artistic collaboration and romantic involvement of a succession of famous and talented women. His art was intimately bound to his personal life to an extent that renders them almost inseparable. He refused to be restricted by conventional notions of reality and recognised the co-existence of a variety of states of being. Creativity flowed through everything he did and recognised few boundaries of genre or medium. His legacy lies not only in his extraordinary body of work, but in the celebration of freedom and spirituality in which it was given existence. He died, aged 82, on 10 June 2019 at Whipps Cross Hospital in East London. He is survived by his children: Sian, Tamsin, Harry, Joanna, Leila, Charlene and Rosetta.

Posted on Friday 14 June 2019