WATCH: Life at DMU - 1970s style!

It’s fuzzy, gloomy and ever-so-slightly wobbly – but while it may not win any awards for cinematography, it’s a golden glimpse of a lost Leicester.

The film below is snapshot of student life at the old Leicester Polytechnic in the mid-1970s, chronicling a campus in stark contrast to the gleaming £136 million transformation of today’s De Montfort University.

Scenes include views of the brutalist architecture of the now-demolished James Went tower and the waterfront William Rowlett Halls of Residence, plus a high-rise ride in the non-stop paternoster lift of the Fletcher building.

It was shot in late 1973 and early 1974 by student Andrew Taylor, who had one eye on his viewfinder and another on posterity.

“I was conscious that one day I’d want to look back on my time in Leicester,” he says, “and that the old Leicester was being demolished in haste.

“I used the film camera as if it was a stills camera, trying to guess which scenes I might value in old age.”

After a year working in industry, Yorkshireman Andrew had arrived as a fresher in Leicester in September 1973 to study electronics.

“The first thing I noticed about Leicester was a faint fusty smell such as you’d get in a railway tunnel,” he says. “London has the same smell. Closer to the Poly, this gave way to the smell of shoe-making. The industry was in decline but there were still one or two factories in production. The city’s layout was easy to memorise and I heard a Leicester accent for the first time, me duck.

“I was late arriving and I spent two days trekking in search of digs because the halls of residence were full, so my Freshers’ Week was compressed into about half an hour.

“All the various clubs and societies had their stalls set out in Hawthorn Hall. I did a quick circuit, made a mental note of what was on offer and slumped into the Poly bar for a beer.”

But however he had pictured life as a student, he probably didn’t imagine it quite as it actually began: Andrew spent his first term lodging in a cottage in the south-west Leicestershire village of Huncote.

“It had a village shop and a pub, but buses were infrequent,” he says. “After missing my 10 o’clock bus one Saturday night and having to walk back to Huncote as I had no money left for a taxi, I decided I would pester for a room in William Rowlett.”

The pestering paid off, although the no-mod-cons character of 1970s student accommodation would come as a rude shock to today’s undergraduates.

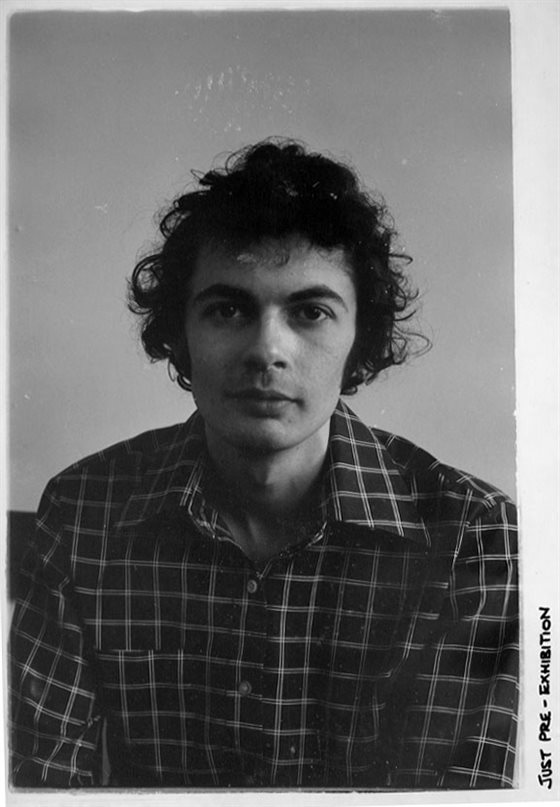

“The trick in William Rowlett was to leave a wet towel in the sink at night or you’d wake up with a dry throat,” Andrew (pictured below) says. “It had a detached TV room too – a source of endless argument about which programmes to watch.”

Later, he moved in with friends to a flat above a shop on Braunstone Gate. It was a workaday street back then, with a couple of pubs, but none of the bars and restaurants that now line its pavements.

“Braunstone Gate was a feeder road to the M1, and the constant stop-start of heavy traffic rattled the windows. When the houses and derelict church behind King Dick Road were demolished, homeless mice took up residence with us.

“There was no heating, the general condition of the place was poor but we lived there until graduation. The rent was £10 pounds a week in total, for all the occupants.”

Andrew’s course centred on the Hawthorn building, then shared by the engineering and pharmacy departments.

“The building reeked of pharmaceuticals but we forgave it that since it had such architectural presence.

“Classrooms had high window sills and radiators fed by cast iron pipes. There was a stationery shop on the main staircase and the college library was reached via several flights of stairs. An occasional descent into the depths of the building was required to reach the electrical and mechanics labs.

“Our Maths classes were in the new James Went tower, as was the computer centre. We shuttled back and forth across the quad carrying bundles of punched cards – computer programs!

“Hawthorn had its own snack bar selling tea, coffee, beef and onion pies of dubious quality and grated cheese cobs.

“A cob, I discovered, was a crusty tea cake. I’ve been hopelessly addicted to Red Leicester since that time.

“The campus restaurant was in Newarke Close but the atmosphere and indifferent food led me to eating in the Newarke Cafe just around the corner, where two wonderful elderly ladies cooked old-fashioned food in a quiet atmosphere.”

Back then, the Poly bar was on the ground floor of the Fletcher building. It was run by a manager called Reg, Andrew remembers: “He came across as the stereotypical London pub landlord.” There was a dartboard, table football, and later, the arcade game Pong.

At the time, the Poly’s Students’ Union was based in a building in the Newarke. “It had no catering facilities,” says Andrew, “and consisted of offices, a meeting room and a front room on the first floor which would be occasionally hi-jacked for impromptu parties.”

The new Student Union Arena was completed in Andrew’s second year and was quickly dubbed ‘the tin shed’ because of its metal cladding.

There was a huge concert hall and stage, a small restaurant and snack bar, a bank, and the new Poly bar - with Reg still at the helm.

“There was also a gift shop,” says Andrew, “selling T-shirts and badges with slogans such as ‘legalise pot’, ‘ban the bomb’ or ‘avoid Lloyds’ – slogans by then considered quaint.”

So what was student life like back then?

“I suppose the answer is ‘whatever you made of it’. Some people locked themselves away and studied hard. Others were out on the town. The trick was to find a balance, but money - or rather the lack of it - was always a problem.

“We had student grants, so no concerns about paying back loans, but grants were slim and students learned to wear cheap clothes, improvise furniture (bricks and salvaged floorboards made excellent shelves) and find cheap meals.

“A few of us supplemented our grants - some found bar work; I worked concerts. Some of the ‘student life’ clichés were true – many students burned joss sticks (to disguise the smell of damp), had a candle in a wine bottle, and covered their walls in music posters or fantasy scenes by Roger Dean.”

Andrew’s favourite haunts included The Magazine pub on The Newarke, The Black Horse on Braunstone Gate - “where locals played dominos in smoke-filled rooms on Sunday, before heading home for lunch” – and the Free-Wheelers nightclub in Churchgate.

After seeing prog-rockers Gentle Giant at the Fresher’s Ball at the Palais in Leicester – “my first experience of a live band” - Andrew joined the Ents committee at the union and immersed himself in a world of booking groups, running discos and taking money on the door, with the occasional nocturnal foray into the city for clandestine fly-posting trips.

Andrew and a group of friends from the Ents committee soon found themselves being hired by promoters to work as stage crew at venues beyond the Poly Arena, including De Montfort Hall, Granby Halls and Bingley Hall in Stafford.

They called themselves the Gophers. “We ended up working once or twice a week, helping ‘roadies’ to unload trucks and set up the sound and lights, only to dismantle it all at the end of the night.

“After Gentle Giant, the only bands I paid to see were Family on their farewell concert in Hawthorn, Genesis, Yes and Roxy Music at DMH in late ’73.

“After that, I worked for every concert. There were more than 150 in total. The memorable ones? Bowie, The Who at Granby Halls, Pink Floyd at Bingley Hall, Rod Stewart at Granby Halls – including a chance encounter with Britt Ekland - Eric Clapton at DMH, darts and beer in the Magazine with Lindisfarne, and a disco at the Poly Arena by the gentleman of rock, John Peel.”

Andrew got into film-making by accident. He was tramping around Sheffield one day, looking for a cheap camera.

“I couldn’t find anything affordable but the last shop had a battered movie camera in the window - a Chinon super-8 camera, with a sticky light meter. The shopkeeper seemed pleased to get rid of it. He threw in two cans of date-expired film, shook my hand and wished me luck.”

The final cut on his Leicester Poly film came courtesy of an editing machine bought from Boots.

“You cranked the handle to spool the film across the gate. Film was cut with a razor blade and the scenes joined together with self-adhesive splices. These splices, I was warned, would not hold for more than six months. They’re still holding after 44 years.”

In 2010, he uploaded his Leicester Poly film to YouTube, along with another film shot in Braunstone Gate, plus footage from a trip to the USA featuring shots of mid-1970s New York and Boston.

“I’ve had a dozen requests from US film companies wanting to use the New York material, precisely because it is old, rough, and nostalgic,” he says.

Filmmaker Mark Craig used some of the Leicester clips for his film High Hopes which traces the fortunes of some of his former classmates at Leicester Poly.

Following an MA in Industrial Design at the Poly, Andrew’s career took him from Marconi Avionics in Kent to a design consultancy in Northampton, dreaming up products for the likes of Vidal Sassoon, GEC, and Electrolux and then BT Labs in Suffolk, where he played a role at the sharp end of consumer technology, from mobile phones to the internet.

“I’m now 65, back in Barnsley and semi-retired,” he says, “which is a euphemism for too old to move to the US and too dumb to learn Mandarin.”

And has he been back to Leicester since he left?

“Only once, in the mid-1980s, soon after the new ring road opened. After going round the ring road twice I realised there were no signs pointing to the centre. It was at this time that broadcaster Terry Wogan started to talk of the ‘Lost City of Leicester’.

“I did eventually reach my goal, but it was near De Montfort Hall, and I didn’t get the chance to look at the Poly or Braunstone Gate.”

Posted on: Wednesday 29 May 2019